Things have picked up again and I thought I’d start by reflecting on my resolutions so far. I’m not doing perfectly, but the one I am really pleased with is the social media one as I thought it would be really difficult, but I’m really enjoying not going on it and keeping it to just a specific time. The ones I’m finding more difficult are putting things back where they belong (currently a bunch of jewellery beside my bed) and managing portion sizes (because I’m used to eating a certain amount and not in the habit of having regular snacks, so tend to be extra hungry come dinner time)! Sleep is still an issue and I’ve found allowing for spontaneity difficult too.

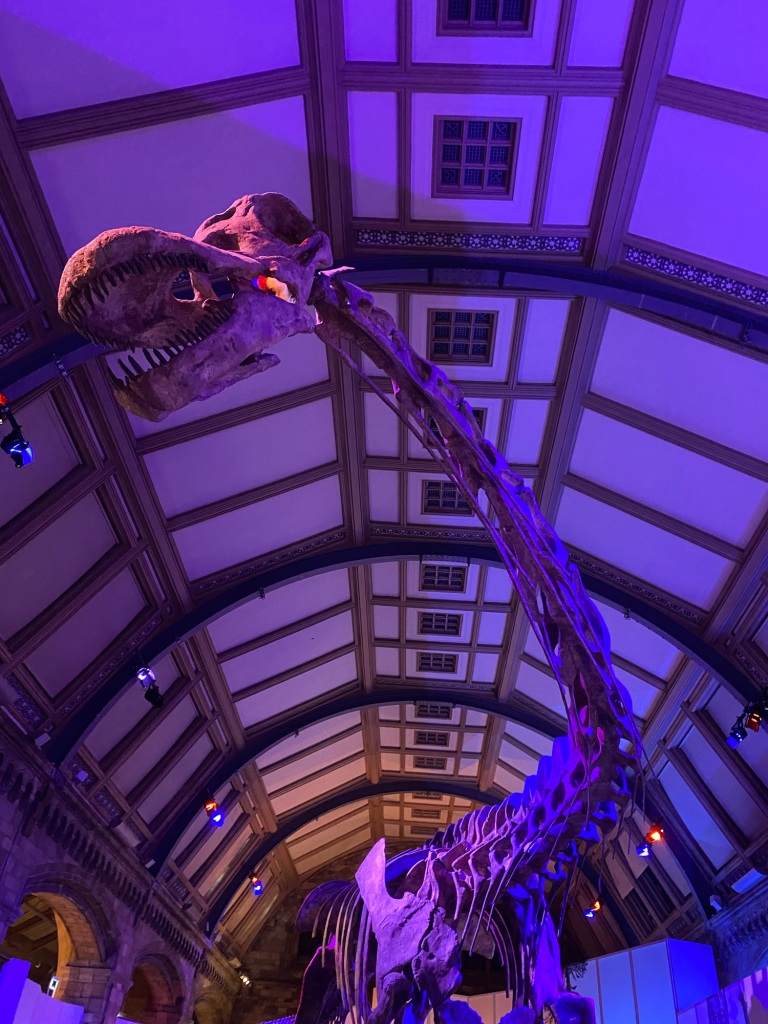

Last Friday I wasn’t working, so I went to three exhibitions! I’ll write in more detail about each of them on my Instagram at some point (it will take a while with my designated day), but it included the Titanosaurus exhibition at the Natural History Museum, where I learnt a lot of interesting things, but didn’t get to go on the games as kids were hogging them! I saw Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas at Tate Britain, whose work I had studied at college. After a hot chocolate break, I went to Re/Sisters, at The Barbican, which was so extensive it took me two hours to get through!

I spent most of the weekend getting on top of things for the week ahead, but also went for a spa day with my mum, which was lovely! I’ve been to the Montcalm a few times, and this time we had Sunday roast at the rooftop restaurant The Aviary, which was delicious.

This week it’s all be back on: admin for She Grrrowls events (with a major hiccup to sort out), tutoring clients, university, clinical placement, essay and debate research and writing, and writing a new ACE application. Then on top of that, trying to keep on top of household chores. I’m pretty zonked and looking forward to a relaxing bath tonight!

Watching: Da Vinci’s Demons, The Traitors, The Simpsons

Reading: The Revealing Image by Joy Schaverian, Approaches to Art Therapy by Judith Aron Rubin, and Little Boxes by Cecilia Knapp

Podcasts: Creative Codex, On Being

Music: Pinhanı

Again, if you’re able to share or donate to my crowdfund as I train to become an Art Psychotherapist, or buy some books, please do!